Kids' Guide: What Is Neurodiversity?

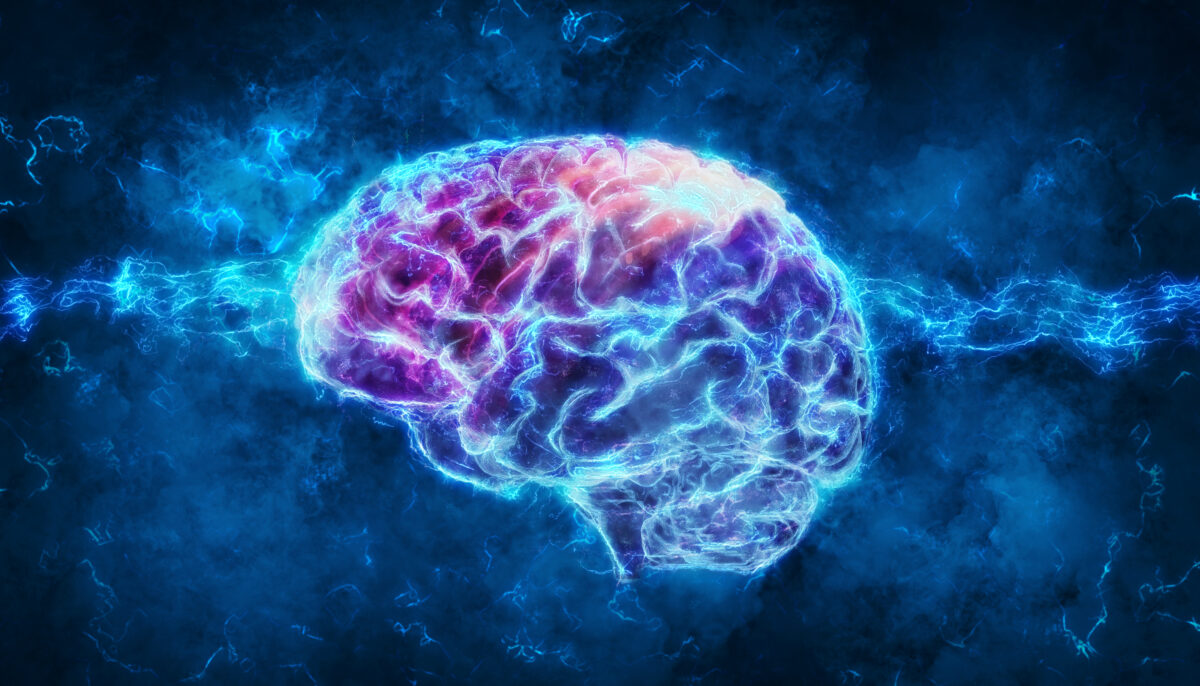

Neurodiversity: it’s kind of a fancy word, isn’t it? Well, the meaning of this word is simple: Neurodiversity refers to the fact that every brain in the world is unique, and no brain is better or worse than another.

But first, what is the brain? The brain is the organ that makes sense of the world around you and tells your body what to do. Every time you think, speak, listen to music, walk or run (you name it!), guess what is helping make it happen? If your answer was the squishy, three-pound organ inside your skull (aka, the brain), you’re right! Your brain and body work together every single day, all day long, to help you do all the things you do—even things you can’t control, like digesting your food!

And what do we mean when we say every brain is “unique”? Every brain works in its own specific ways, and every brain has its own set of strengths and weaknesses. However, most brains also have things in common with each other. For example, most kids have brains that allow them to read, write and do math by a certain age. Most kids’ brains also enable them to communicate, interact and play with peers. Kids with this type of brain are called “neurotypical.”

There are some brains that are even more unique than neurotypical brains: They are called “neurodivergent.” Kids with neurodivergent brains learn and experience the world differently than neurotypical kids. Because of that, they sometimes need extra help and support at school, which is called “accommodations.” But just because neurodivergent kids might need accommodations, it doesn’t mean there’s something wrong with their brains.

Let’s look at what all this means.

Jack, a third grader, is great at memorizing sports trivia and is a master Lego builder. However, reading is difficult for him. He often needs to re-read a paragraph a few times to understand what it says. He confuses letters that look similar, like b and d, or letters that sound similar, like d and t. Because of these difficulties, he needs more time than his classmates to complete his schoolwork. Sometimes the teacher lets him listen to reading assignments on the computer and gives him visual aids (like drawings) to help him understand the text. She also gives him reading guides and highlights important words and passages. With the help of these accommodations, Jack can do his schoolwork and learn right alongside his peers.

Luna, a fourth grader, is an avid reader but needs help with math. She often confuses symbols like the plus, minus, multiplication and division signs. She can’t do mental math and needs to use her fingers to count. The teacher helps Luna by highlighting and circling important words, signs and numbers on her math worksheets. She also gives Luna charts with math facts and multiplication tables. Like Jack, Luna needs more time than her classmates to finish quizzes and tests.

Hazel is a third grader who loves reading fantasy books and historical fiction. She enjoys going to school and learning new things, but sometimes has a tough time working in groups. Whenever things get loud in the classroom, Hazel can get a little upset. The teacher helps by providing noise cancelling headphones during noisy activities and by letting her take quizzes and tests in an empty classroom. Although Hazel knows many words and can read and write well, sometimes she has a tough time communicating with peers. During recess, she needs time alone to decompress and get her brain ready for learning again.

Felix is a talkative and energetic third grader. He likes all subjects, especially science and math, but it is difficult for him to sit still and do schoolwork for too long. That is because Felix’s body needs frequent movement breaks for his brain to “calm down” and focus. So, whenever he starts feeling “twitchy,” Felix lets his teacher know, and she helps him pick a calming strategy. Some of his strategies include using a fidget (like a spinner or a squeeze ball), doing wall pushups or sitting on a therapy ball instead of a regular chair.

Do you know a kid who is a little bit like Jack, Luna, Hazel or Felix? Lots of people do! Do you sometimes feel like at least one of them? Well, that is totally normal—to be different is a natural part of being human.

Doctors and scientists have been studying the brain for a long time. Now, we know that many people who are neurodivergent also have things they can do well and without help. What’s more, we can make things easier for people whose brains or bodies work differently by making simple changes to our environment. For example, if a kid has a tough time staying focused in the classroom, we can have her sit up front, close to the teacher, or try one of Felix’s calming strategies. If a student can’t write or draw with a pencil, he or she can use a computer to type and complete classroom assignments. If a kid needs a wheelchair to move around, we can make sure the school property has ramps and elevators.

Doctors and scientists have been studying the brain for a long time. Now, we know that many people who are neurodivergent also have things they can do well and without help. What’s more, we can make things easier for people whose brains or bodies work differently by making simple changes to our environment. For example, if a kid has a tough time staying focused in the classroom, we can have her sit up front, close to the teacher, or try one of Felix’s calming strategies. If a student can’t write or draw with a pencil, he or she can use a computer to type and complete classroom assignments. If a kid needs a wheelchair to move around, we can make sure the school property has ramps and elevators.

Some neurodivergent kids have brains that are so unique they require even more accommodations than Felix, Jack, or any of the kids we described. Some of them communicate differently and don’t use words the way neurotypical kids do. Others learn things at a slower pace and need different teaching strategies to understand the material. Many neurodivergent students need an aide to help them during the school day. And there are those who do much better in classrooms that are specially designed with their needs in mind, with teachers who are trained to teach students who learn differently. Sometimes, neurodivergent kids need to attend schools that were specifically created for students with learning differences.

On the other hand, there are kids whose brains are so unusual, they can learn things extremely quickly—much quicker than kids their age and even some adults. Have you ever seen news stories about kids who graduate from high school at the age of 9 and start college before they are even 10 years old? Well, that’s a neurodivergent kid for you!

So, why is it important to know that there are different types of brains in the world? Well, for one thing, because YOU have a brain! If you feel like you learn differently and would do better at school with more support, it would be helpful to talk with an adult about it. If you know someone who is neurodivergent, it’s important to understand that his or her differences are not problems. We all have unique brains and different ways of learning and experiencing things. And that makes life all the more exciting!

Questions

- Some brains are good at memorizing things. Other brains are good at imagining and creating stories or paintings. Some brains are good at figuring out and understanding what people are feeling. Other brains are great at understanding math or working with computers. What are some of the things your brain is good at?

- Most brains have a thing or two (or three, or more!) that are tough for them to do. Jack is great at memorizing sports trivia, but reading is difficult for him. Luna is an avid reader but struggles with math. What are some things that are hard for you?

- What does it mean to have a “neurotypical” brain?

- What does it mean to have a “neurodivergent” brain?

- Sometimes, a neurodivergent kid can have a tough time doing certain things, such as staying focused in the classroom. What are some accommodations a neurodivergent student can get at school?

- Being neurodivergent can also mean having unusual abilities, such as learning how to read at the age of 3, for example. Can you think of other similar examples?

- Do you know someone who is neurodivergent? Now that you have this knowledge, do you feel like you understand them a little better?

Embracing Difference

One of the most empowering insights I’ve reached as a special needs parent was the realization that differences in brain function are natural, ever-present aspects of the human experience. They are as old as humanity itself.

It took me a while to embrace this view, partly because my neurodiverse child’s struggles—such as her social communication difficulties and motor clumsiness—are undeniably and inextricably tied to her neurodiversity. But eventually I came to view her difference for what it is: her unique way of filtering and processing information, communicating her impressions, and functioning in this world.

I’ve recently found myself wondering: Is my anxiety making my child anxious? Or am I anxious because I have such an anxious child?

I’ve recently found myself wondering: Is my anxiety making my child anxious? Or am I anxious because I have such an anxious child?

Tom has a piano at home, and he likes to play it to soothe himself after a rough day. This is the perfect opportunity to do the same thing at school. He stands in front of the xylophone for a moment, grabs the mallets, and starts playing a classical tune.

Tom has a piano at home, and he likes to play it to soothe himself after a rough day. This is the perfect opportunity to do the same thing at school. He stands in front of the xylophone for a moment, grabs the mallets, and starts playing a classical tune.